On Dec. 6, Canada will commemorate the 30th anniversary of the massacre at l’École Polytechnique in Montreal, when 14 women were killed because they were women. There can be no doubt about the motivation. When a 25-year-old man walked into a classroom full of student engineers carrying a knife and a legally purchased assault rifle in a garbage bag, he knew what he was going to do.

“The feminists have always enraged me,” he wrote in a suicide note. “They want to keep the advantages of women … while seizing for themselves those of men.” He listed the names of 19 other women he was hoping to kill, if he had the time.

At l’École Polytechnique, he walked into a classroom where the engineering students were giving an end-of-term presentation. He separated the men from the women, and shot all nine women in the room, killing six. He shouted;

“You’re all a bunch of feminists, and I hate feminists.” He continued his rampage through the school, before taking his own life.

The source of his rage could not have been clearer. He wrote it down and spoke it out loud. And yet, in the aftermath of the shooting, there was an effort to explain away his atrocity as anything but misogyny. He was mentally ill, the traumatized child of an abusive father, rejected by women and the army and the school where he committed his crimes.

And those things are true. But what is also true is that he – for whatever reasons, internal or external – had developed a hatred of women that became lethal.A woman fights back tears at a memorial in Toronto in April, 2018, the day after a man drove a van into a busy stretch of Yonge Street.

One year later, l’École Polytechnique’s director asked the media to commemorate the killings not with anger or protest but “through reflection, and silence.” I thought about this in April, 2018, when I went to visit the memorial that had sprung up in North Toronto to mourn the 10 victims – eight women and two men – of a van attack earlier that week (16 people were injured). There were flowers and candles and messages, most of them on an anodyne theme of resilience. Toronto was strong. Only in one corner did I find a rain-soaked note that indicated this attack had been ideological in nature: “Yes it was terrorism. Women’s rights are human rights. (Anti) social media is complicit.”

All we knew at that point was that the alleged attacker had posted a message to Facebook before he rented the van and began to mow people down. “The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” That message was cryptic then, less so now, as we begin to understand the community to which the van driver claimed loyalty: incels, short for involuntary celibates.

We are not naming these men who took the lives of 24 people. We are not naming them in order to deny them what they wanted most – notoriety, and the ability to inspire others like them.

The Montreal massacre victims. Top row: Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, Annie St-Arneault, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau and Barbara Daigneault. Middle left: Annie Turcotte. Middle right: Geneviève Bergeron and Michèle Richard. Bottom row: Anne-Marie Edward, Anne-Marie Lemay, Maryse Laganière, Maud Haviernick, Sonia Pelletier and Maryse Leclair.

The Toronto van-attack victims. Top row: Andrea Bradden, Anne Marie D’Amico and Geraldine Brady. Middle left: Betty Forsyth, Ji-Hun Kim and Renuka Amarasinghe. Middle right: So He Chung. Bottom row: Dorothy Sewell, Chul Min (Eddie) Kang and Munir Abed Najjar.

Two of the worst mass killings in Canadian history sprang out of misogyny.

When stated as baldly as that, it seems shocking. It seems shocking because very few people have framed these tragedies as extremist acts, or hate crimes, based on hostility toward an identifiable group: women. Indeed, the connection between extremism and misogyny has been overlooked, in academic studies and law. But what if we did start thinking about it that way?

What would our society look like if we recognized misogyny as an ideology, one that is a deadly threat to half the population? We know that right-wing violence is on the rise, and that the various forms it takes – white supremacist, incel, nationalist – share misogyny as a binding tenet. Right-wing terrorism and Islamist extremism might not have many things in common, but anti-woman sentiment is one of them, even if it seldom is acknowledged.

Sexism is not new, but virulent forms of radicalization are, and they appeal to men who feel marginalized in an unfair economic system and blame women, along with migrants, for their woes.

These violent acts are intended to be sequential – one killer drawing inspiration from another – and yet lawmakers regard them as the crimes of an individual, not the consequences of an interconnected and poisonous ideology.

Incel communities are diverse and far-flung, united in moaning over their inability to get laid. At the most innocuous, they are rich in irony and memes, engaging in one-upmanship (or downmanship) over who is the more loathsome and pathetic. They share a sense of grievance at a mythical world they’ve constructed, in which good-looking women trade sex for status with equally good-looking – and, crucially, tall – men, while rejecting the “gentlemen” in their midst. The gentlemen, in this piteous scenario, are the incels. Except they are not gentlemen. At their worst, they are deadly; they urge one another to acts of violence.

Earlier this year, the Toronto police released a three-hour video of the interrogation of the 25-year-old man accused in the Yonge Street attack (he is charged with 10 counts of first-degree murder, 16 counts of attempted murder and will be tried by a judge in 2020). The man sits in a white prisoner’s jumpsuit, occasionally fiddling with a bottle of water. A former computer-science student, he talks about his interactions on incel forums on reddit and 4chan. He describes being rejected by a girl in 2012, and being laughed at by a group of women at a Halloween party in 2013.

He says, “I felt very, very angry. I considered myself a supreme gentlemen. I was angry that they would give their love and affection to obnoxious brutes.” He adds, “I know of several other guys over the internet who feel the same way but I would consider them too cowardly to act on their anger.”

He speaks of an “incel rebellion,” and hopes “that I would inspire future masses to join me in my uprising.” This is crucial: While the vast majority of the movement may be content with slagging off women online, for a critical few, the violence moves to the real world, where it becomes deadly.

He cites Elliot Rodger as an inspiration, calling him the “founding forefather” of the incel movement. Mr. Rodgers killed six people and injured 14 others in Isla Vista, Calif., leaving behind a manifesto in which he talked about his desire to wreak revenge on women who’d rejected him. Since then, there have been five deadly incel attacks in North America, according to the Global Terror Index 2019. Some mass killers, such as the shooter at Parkland High School in Florida and the one at Umpqua College in Oregon, have cited Mr. Rodger as an inspiration. On some incel boards, the man who killed 14 women in Montreal is hailed as a hero, the original incel. The poisonous thread moves between decades, kept alive by the aggrieved. What they have in common is misogyny as an ideology.

You can take misogyny to mean, in its most basic form, hatred of or hostility toward those who identify as women, as a group. Beyond that, it is the concept that women are less human than men, less worthy of dignity. That women exist to supplement men’s existence, as objects of pleasure or subjugation. The Cornell University professor of philosophy Kate Manne presents a picture of a society in which white men are considered “human beings” but women are “givers,” which sheds light not just on incels but on much extremist ideology (and, to be honest, much of daily life): “A giver is then obligated to offer love, sex, attention, affection, and admiration, as well as other forms of emotional, social, reproductive and caregiving labour …” she writes in her 2017 book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. “Misogyny is then what happens when she errs as a giver – including by refusing to be one whatsoever – or he is dissatisfied as a customer.”

This is not an academic argument. It’s a matter of life and death.

Four countries, four memorials to deadly acts of hate: 2011’s terrorist attacks in Norway; March of 2019’s mosque attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand; an anti-Semitic attack in Halle, Germany, this past October; and a mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, this past August. The attackers in all four cited ‘replacement theory,’ a discredited far-right belief based on racist and sexist assumptions, among their motives.

When Barbara Perry first began investigating right-wing extremism, one of the things she highlighted was the way that misogyny was a core ideology that bound disparate groups.

“I highlighted this idea of patriarchy and control of women’s sexuality and anti-feminist sentiment,” she told me recently. “These are pieces that often get overshadowed by the emphasis on the groups’ anti-Semitism and white supremacy.”

Racism, homophobia and sexism are inextricably bound together on the far-right, says Dr. Perry, who is director of the Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism at Ontario Tech University. The far-right believes that “the purity and survival of the white race is dependent on being able to control women and keep white women in line and in the home where they can defend them and impregnate them.”

And incels, she says, are part of this spectrum: “The incel is just one of many columns in the far-right movement. It’s that idea that men should have, by rights, unfettered access to women’s bodies.”

As Dr. Perry says, academics “have only really begun” to study the far-right. The role of misogyny in extremist thought is barely being scrutinized, even though it’s a core tenet of neo-Nazi beliefs, white supremacists and the adherents of the “Great Replacement” theory, which holds that feminism is evil, because it keeps white women from having more white babies.

There’s a direct line between mass murderers who hold such supremacist beliefs, from the one in Oslo to the one in Christchurch. The man who recently committed an anti-Semitic attack that killed two in Halle, Germany, broadcast his rant on the platform Twitch: “Feminism is the cause of declining birth rates in the West, which acts as a scapegoat for mass immigration,” it began.

This summer, Britain’s Institute for Strategic Dialogue issued a report about the threat posed by this sector of the violent right: “The Great Replacement theory is often intimately bound up with misogynistic discussions – with women often being blamed as the drivers of falling birth rates as they step away from traditional gender roles.” It added, “Over all, policymakers have been slow to recognize the threat posed by the extreme right.”

That may be changing, in regards to the threat posed by the far-right – if not necessarily the underlying threat posed by misogyny. Public Safety Canada’s Report on the Terrorism Threat to Canada in 2018 mentioned the Toronto van attack, saying it “alerted Canada to the dangers of the online Incel movement.’’ However, it then went on to downplay the threat of “racism, bigotry and misogyny” in Canada, which “do not usually result in criminal behaviour or threats to national security.”

The newly released Global Terror Index report also mentioned the van attack while discussing the rise of far-right extremism, noting there’s been a 320-per-cent increase in far-right terrorist acts in North America, Western Europe and Oceania over five years.

Given the threat, and the clear thread that binds these disparate hate groups, why isn’t misogyny taken more seriously as a factor in motivating crimes, and sentencing criminals? As Dr. Perry says, a lot of it is down to mindset.

“For lay people, for law enforcement, they don’t really understand what ideology is. They don’t understand that patriarchy and misogyny are ideologies, are world views. They think they’re individual attitudes, and that’s very different.”

Women take part in a die-in in Panama City on Nov. 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. The slogan ‘Ni Una Menos’ (not one less) originated in a 2015 tweet by an Argentine journalist about the killing of a 14-year-old pregnant girl, and has galvanized feminist movements across Latin America ever since.

So, should crimes that target women specifically be treated as hate crimes, or even terrorism? Joshua Roose, an Australian academic who studies the intersection of masculinity, religion and extremism, certainly thinks so. His deep dives take him to depths most people never see, into the so-called manosphere of incels, men’s rights activists and MGTOW (men going their own way), an anti-feminist subculture whose members shun relationships with women.

“When you have men who are prepared to go out and actively seek to kill women on the basis of their gender, then that is absolutely terrorism on the basis of gender. I would argue that the incident in Montreal was an act of that.”

Dr. Roose is a political sociologist at the Institute for Religion, Politics and Society at Australian Catholic University, and sits on an Australian government advisory panel to counter violent extremism. He’s working on a book about what he calls “ideological masculinity” – that is, a set of beliefs embraced by some men who feel that women’s increased power diminishes their own lives. Certain men feel threatened by women asking for equality in the public and private sphere, he says – but then some men always have. What’s the difference now?

It is a crippling and explosive confluence of events. Not long ago, Dr. Roose says, men had institutions such as labour unions to provide them with a sense of solidarity, dignity and worth. They might have gone to church for spiritual guidance. There was a good chance they’d be able to afford a home. A decline in institutions that provided self-worth, plus a perceived rise in women’s empowerment, leaves a certain kind of man vulnerable to radicalization, and a certain type of community taking advantage of it. It gives him a place to belong, and a target to aim at.

‘’One thing across the spectrum is that masculinity has been mobilized by populist actors,” says Dr. Roose, citing politicians such as Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, as well as various vitriolic men’s rights groups. “It’s become this pretty extreme discourse that just a few years ago would have been unimaginable.” Based on his research, Dr. Roose worries that “things are going to get uglier, much uglier, in terms of treatment toward women. Radical challenges require radical approaches and solutions. Treating these things as terrorist acts is radical, but absolutely vital to the solution.”

Treating misogyny as an act of terror, or even a hate crime, raises many thorny issues. Who would decide what charges to lay? Would those charges help or hinder a conviction? Would they provide more or fewer resources for investigating crimes?

There’s also an argument put forth by feminist legal scholars that terror or hate-crime legislation is not a useful way to deal with the threat of sexism, on the grounds that it’s so pervasive that the legal system itself has not yet dealt with its anti-female bias.

“Law is not a reliable tool on its own, it’s only one tiny part of a huge social change project,” says Amanda Dale, director of Canada’s Feminist Alliance for International Action. But Dr. Dale agrees with Dr. Roose that we are in the midst of a historically perilous moment. “We’re seeing these populist movements that are based on misogynist ideals. It’s pushback against social equality.“

And, like Dr. Roose, she sees some men losing economically and misplacing the blame at the feet of women and immigrants. “Just look at any of the major Western democracies, and you see the concentration of wealth in a smaller and smaller percentage of the population. Who becomes the target? It’s not the rich guys. It’s the people who look different who are trying to get to the table. It’s a really deadly and violent moment that we’re in.”

In 2016 and 2017, three major acts of violence – a shooting at a Texas church, a bombing at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester, and a shooting at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub – were carried out by men with histories of domestic violence.

Joan Smith wasn’t entirely surprised when she heard from a British police officer that it would be impossible to investigate hate crimes based on misogyny, because there would simply be too many of them.

Ms. Smith, who is the co-chair of the London Mayor’s panel on violence against women and children, has just written a new book examining the relationship between domestic violence and extremism, Home Grown: How Domestic Violence Turns Men into Terrorists. What she found, echoing other research, is that men who commit extremist violence in the name of religious ideology, or commit mass shootings, often have committed acts of violence before – on members of their families. And those warning flags were almost always ignored.

“Because so much male violence is normalized, particularly when it’s domestic, and it’s not really seen as violence, we’re missing something that could actually be a huge warning sign and could help to save people’s lives.”

One of the things that surprised her most was how little research had been done into the connection between violence toward intimate partners or family members, and violence committed on a larger, public scale. “If you see terrorism and mass murder over here, and violence against women way, way over there, then you don’t make the connection.”

Her research uncovered, for example, that in the case of three of the most serious terror attacks in Britain in 2017, four of five attackers had a history of domestic abuse. One example was the 22-year-old man who targeted teenage girls at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester, killing 22. He had mistreated classmates at college, including punching one in the face after telling her that her skirt was too short. He faced no criminal charges – a conviction could have been a red flag for police.

Ms. Smith reels off other instances from around the world – the church shooter in Texas who killed 26, even though his history of domestic violence should have prevented him from buying a gun; the murderer at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, who’d physically and verbally abused his wife. One survey out of the United States says that 57 per cent of mass shootings involve an intimate partner or family member. This year, half of the 20 worst mass killings in the U.S. involved domestic violence, according to an analysis by ABC News.

The phenomenon tracks across extremist ideologies and geography: A new report from UN Women into radicalization in Libya found that “people who support violence against women are much more likely to support violent extremism.” In fact, accepting such violence was the single greatest determinant of whether someone would be drawn to join a terrorist group – more than age, education or religious background.

In Canada, where 148 women were violently killed in 2018 (including the ones in the Toronto van attack), misogyny is considered the primary motivating factor in their deaths, according to the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability. Domestic violence often precedes the killing. For Indigenous women, who are killed at a much higher rate proportionate to their percentage of the population, the situation is much worse. It has, in fact, been called a genocide by the authors of Reclaiming Power and Place, the report into the murders and disappearance of countless Indigenous women and girls.

Ms. Smith would like to see violence on that scale studied systemically, and prosecuted as hate crimes. In her home country, Britain, the Law Commission is studying whether to make misogyny a class of hate crime, following a pilot program that did just that in the county of Nottinghamshire. (The chief of London’s police recently came out against the idea, echoing the concerns Ms. Smith had heard: Her force simply did not have the resources to tackle all gender-based hate crimes.)

“We have to take violence in the home much more seriously,” Ms. Smith says. “Get boys out of these toxic households. And make sure there is a record of men who are regularly abusing members of their families. Most domestic abusers won’t go on to be terrorists or mass shooters, but some will.”

In Montreal and Toronto, plaques honour the victims of the École Polytechnique massacre and the site of the Yonge Street van attack.

What needs to happen in order for violence against women to be seen as the ideological threat that it is? For one, it has to be understood that way. It has to be studied not just in silos, but in a way that acknowledges that misogyny exists on a continuum, moving from online to real life, from movement to movement, from the house to the street.

There is much good work being done, by men’s groups that attempt to deradicalize young men, and by women’s groups that advocate on behalf of victims’ rights. Academics are beginning to study and draw parallels between seemingly disparate extremist movements. The online realm is no longer discounted as “not real life” and therefore no threat. Last year, Public Safety Canada provided $2-million in grants to study the incel movement.

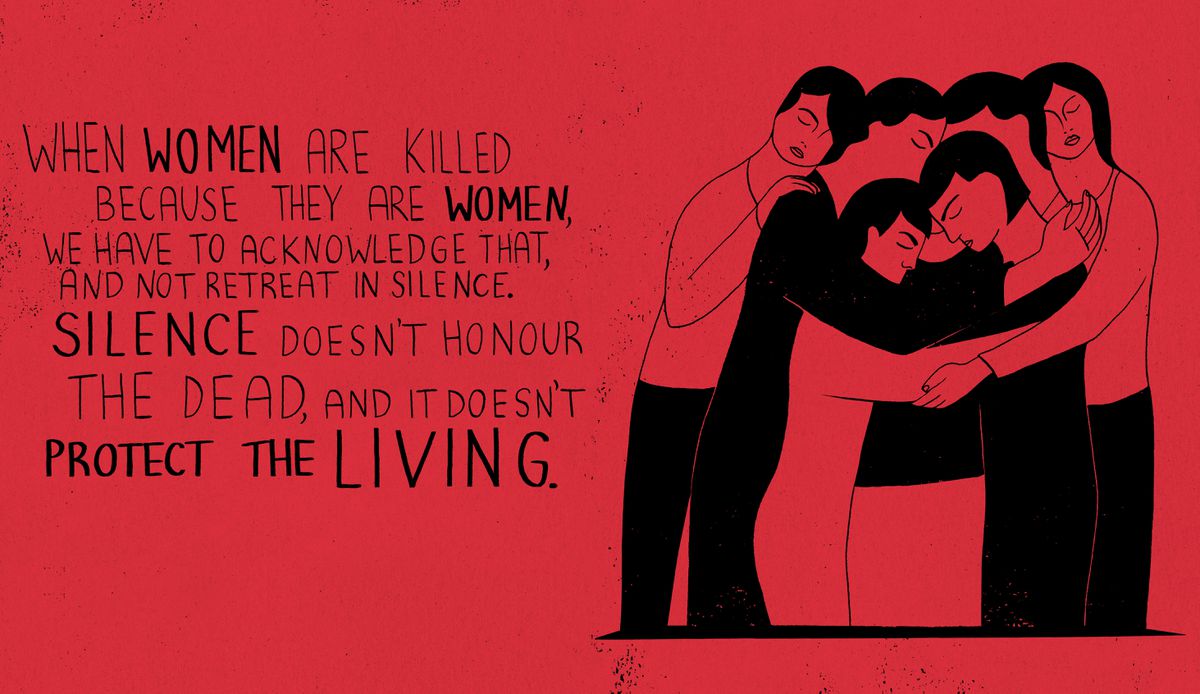

Finally, when women are killed because they are women, we have to acknowledge that, and not retreat in silence. Silence doesn’t honour the dead, and it doesn’t protect the living.

Source; The Globe & Mail

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/XVLDKPPKZ5CCZOTETM25JO7VPU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/ANDQUGFBFFFCRDXRYRJRK3TGP4.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/WRCV7AVYI5BVRF7B77REJNVUZU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CSAZSAUNKNBLJHOORVZHRQTGEE.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/QDJJ4WJYFRHCXN5HBE6EC2GSJY.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/DV2EYRMECNFOTMWEV2YYGBA2BA.jpg)